It all sounded so poetic. So fitting. So right.

After 38 years of orbiting the sun by way of the Great Lakes of North America (Canada 1985-1990, Wisconsin 1990-2003, Minnesota 2003-2023), I was getting ready to, for the first time in my life, leave the humble Upper Midwest and move to the tropics. And before I made that move, before I abandoned all the north has to offer–from its gorgeous summer lake life to its bountiful autumn harvests to its relentless, icy, bitter, frigid, ice scrapey, shovel-filled winters–I would journey with a friend to the one heralded nature spot in Minnesota I hadn’t yet visited in my 20 years in the North Star State, to the one place on the globe where my home of the last two decades and my birth country meet, to what could very well be my last expedition into the nature of the north – the Boundary Waters Canoe Area.

It all started in the summer of 2022. I was with a friend, in a driveway, escaping the backyard chaos of a child’s birthday party for a few moments. The friend was Blake Sundeen. For the previous handful of years, Blake and I had been closer to the acquaintance side of the friendship spectrum, friends only because we share a close mutual friend. Lately, though, through a few conversations at social gatherings, I’d been feeling a stronger connection with Blake, a magnetism toward his energy, and I suspected the feeling was mutual. He was one of the few people I could nerd out with when talking about hiking, trails, nature, wildlife sightings, climate change, and sustainability. We seemed to share a similar outlook on these topics. And so, on that driveway, the idea emerged that we should do some sort of camping trip some time. How fun it would be to go romp around in the woods with someone else who felt as alive in nature as I do!

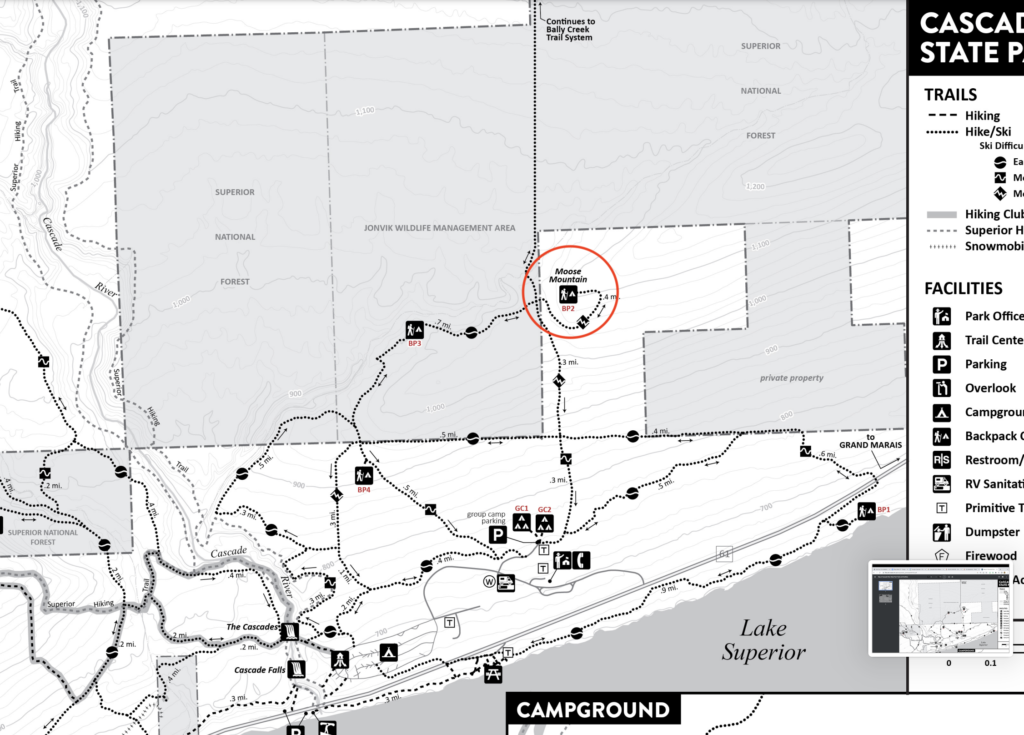

Once I get an idea that I’m excited about, I tend to go full steam ahead with the travel planning and coordination. This instance was no different. Just a couple months later in September 2022, we did go on a camping trip. We brought two other yahoos with us and ventured into a hike-in campsite at Cascade River State Park. It was fun. We hiked a long hike. Only one person did a late-night shaving of a piece of his finger with the axe while chopping wood. We had a good time.

Leaving that weekend at Cascade River, though, I did not feel satisfied. It wasn’t quite the wilderness experience I was hoping for. It was too easy, too comfortable. When I’d told my travel companions what I was planning for the long weekend menu–dehydrated meal packs for dinner (which are a camping luxury in my opinion), tea for breakfast, trail mix for lunch, and granola/protein bars to fill in the cracks–they didn’t say much, which I assumed meant everyone agreed with the plan. But when we arrived at the campsite and everyone unloaded their gear, I was disappointed to find the crew had vastly overcompensated for my minimalist meal plan by bringing a mass quantity of packaged, processed food. This alone gave the entire experience a cushy, glamping vibe that left me wanting more out of what could be my last nature experiences in Minnesota.

BOUNDARY WATERS

In the months that followed, Blake and I planned a trip to the Boundary Waters. Over egg foo young one day, we discussed some ground rules, a handful of expectations that we each had for the experience to be fulfilling for both of us:

- It would be just the two of us

- We will actually have a minimal food plan (especially since we’d have to carry everything)

- We’d be gone for a total of five nights – first night at the outfitter and then the next four nights out in the wilderness.

- We would go at the end of May, soon after the lake ice would melt, but hopefully before all the mosquitoes and lake flies would hatch. It might be chillier, but that was our available time window.

- We’d set an ambitious route covering a lot of miles since we would be a lean and nimble crew of two, but we’d be flexible to make changes to the route depending on the conditions of the weather, our bodies, and our desires once we got out there.

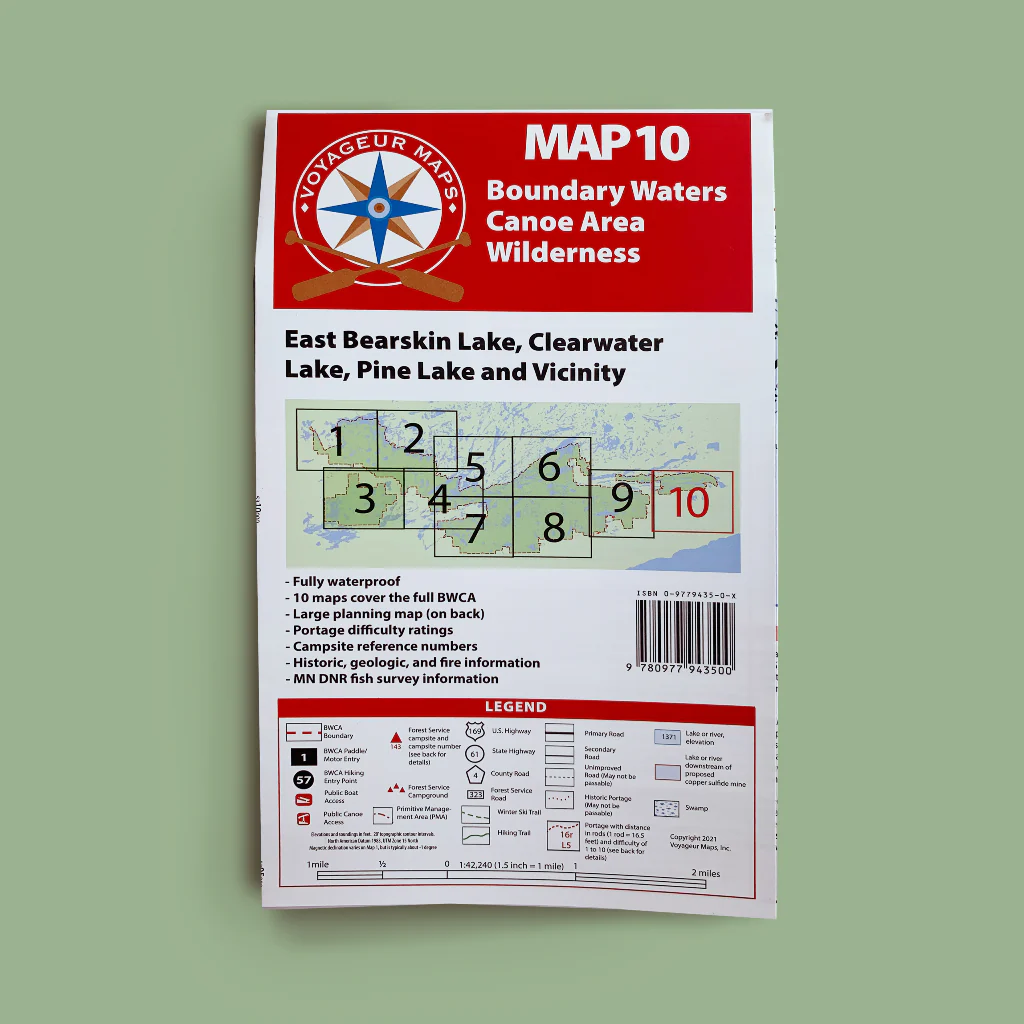

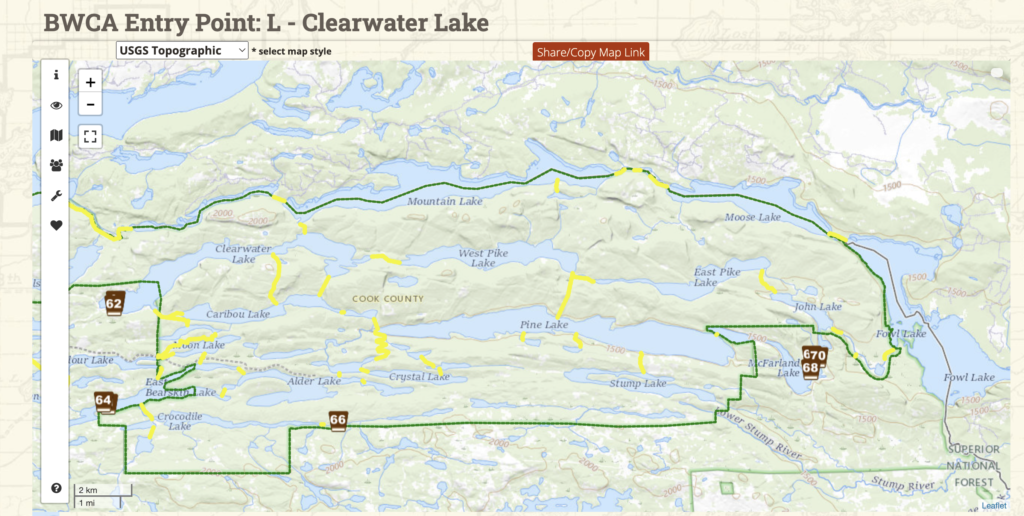

- Our entry point would be at Clearwater Lake in Zone 10, the Northeastern-most zone in the BWCA. From there, we would paddle further north and east through Mountain Lake and Moose Lake, two long lakes that touch both the United States and Canada. After that, we’d circle south and then west through a handful of other lakes to make it back to Clearwater Lake in five days.

Day 1 – Tuesday – Travel Day

Night one we spent at Clearwater Lodge. On the way up we stopped at a sporting goods store to purchase the cheapest fishing rods we could find. We arrived late at the lodge, and we accidentally squatted in a camper cabin because we couldn’t find the bunkhouse (the cheaper option we’d reserved) in the dark. The cabin was not made up for guests; the blankets were wrapped up in bags and there were some loose tools scattered about, but there were two beds and a roof, so it sufficed for a shelter.

Day 2 – Wednesday – First Day of Paddling and Setting Up Camp

We paddled Clearwater Lake and almost all of Mountain Lake. Camp at night one was a bit of a disaster. We were both using hammock setups for sleeping. No tents. My genius packing idea was that I’d bring one regular tarp (for the ground or as an all-purpose item) as well as the rain fly from my tent, which I’d set up over my hammock. It keeps the rain off my tent, so of course it’ll keep the rain out of my hammock, right? Well, as I set up my sleeping rig I realized I broke one of the rules of wilderness survival–don’t let the first time you try your gear be when you’re out in the woods. The tent fly was not shaped as a simple rectangle; it had a custom shape meant specifically to fit the tent it came with. So, I got wet. So far, so good.

Day 3 – Thursday – Fishing in Moose Lake & The Luxor

After portaging and paddling into Moose Lake, we made a choice to stay in Moose Lake for the day. It was supposed to be one of the best fishing lakes in the entire Boundary Waters, and we’d just spent some dough to buy our amateur fishing gear, so we decided we’d have an easier, more luxurious day with a shorter paddle to make more time for fishing. We stopped at a campsite, unloaded, and then took the canoe back out to try our hand at fishing. An hour and several inlets later… no bites. No nibbles. Nada.

At camp, my sleeping situation was vastly improved with some tweaks–I realized the tent fly wasn’t going to work and started using my regular tarp, which worked much better. It started to rain as we sat around the fire, so Blake showed me how to prop up our other tarp over the fire using long tree limbs. Being able to stay out by the fire amidst a downpour felt so luxurious out in the wilderness we dubbed this campsite The Luxor.

And while we didn’t see any moose around Moose Lake, we did have a friendly visitor join us late around the campfire, a large bunny we named Harold. (Get it?) He was massive and seemed to enjoy our company.

We had so much free time at this camp that Blake carved a functional bow and arrow.

Day 4 – Friday – The Day it All Went South. Or Was It West?

Choosing the shorter paddle day on Day 2 meant we were going to try to put some miles behind us on Day 3. We were charged up from The Luxor and ready to move. The plan was to paddle east into North Fowl and South Fowl Lakes, cut back in west to Royal River and Royal Lake, and then loop south into Little John Lake, then cruise through McFarland Lake, and make it to Pine Lake where we’d make camp at the first desirable campsite we’d see. It was an ambitious route covering a lot of distance, but after our more relaxed day at The Luxor, we had gas in the tank, and this way we’d be able to meander our way across the large Pine Lake on Saturday and take our time to choose a superb campsite for our last night in the woods.

Things started off well. It was a bit sad to tear down The Luxor, but I was already looking forward to recreating it, heck, maybe even upgrading it, at whatever campsite we’d choose next. I was now a champion of the Boundary Waters, ready to tackle anything.

Getting into North Fowl and South Fowl lakes, we noticed two things. One, we understood how those lakes got their names; all of a sudden there were flocks of birds everywhere! Two, I observed just how stark the difference is between a lake area that is protected by the Boundary Waters Canoe Area and a lake area that is not. There were cabins clogging up the shoreline. My eyes were opened to just how wonderful it had been to be making our way through complete, undeveloped wilderness.

After the Fowl Lakes we successfully found and portaged into Royal River – the turnaround point of our expedition, the point where we’d stop going east, away from our entry point, and begin heading west back to our outfitter. We got into Royal Lake, which is essentially just a large opening in Royal River, and proceeded northwest where, after a portage, the river opens into John Lake.

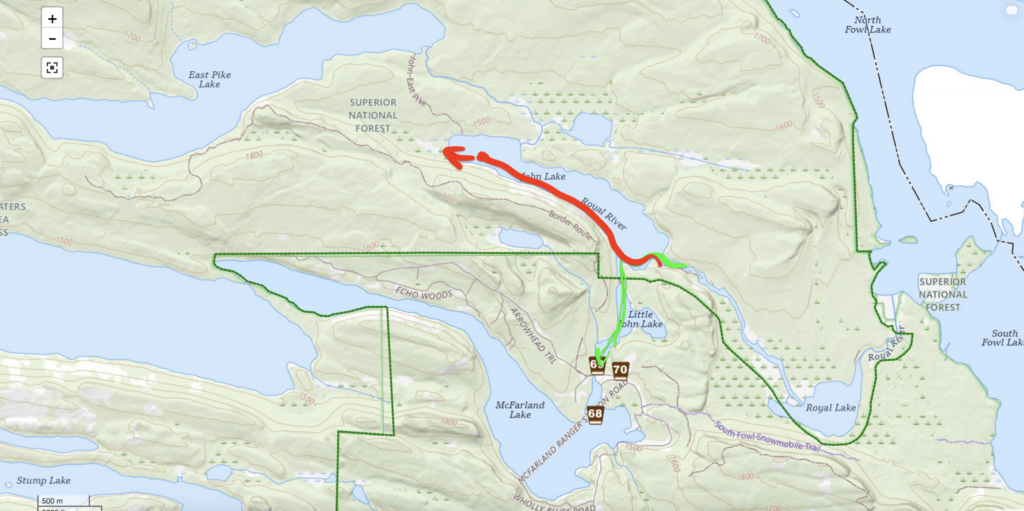

Note the Fowl Lakes on the east and the point where Royal Lake and Royal River then allow you to loop back westward

As we geared up for the next paddle, we checked our map and saw that we would have only a short paddle west to get from the opening of Royal River into John Lake to the narrow passageway that leads to Little John Lake, where we’d dip south for the portage into Little John. We began paddling and hugged the left bank of the lake, which would lead us to that narrow passageway.

Now, we paddled for what felt like a short while to us and made it to the area that we thought was the narrow channel we were looking for. It had been our experience looking for the other portages thus far that they weren’t always easy to find. They aren’t well-marked. It’s the wilderness out there! You have to read the shape of the land, the topography as well as the directions on the map, in order to find where the likely portage spot is.

The water started getting shallow. Reeds and tall grasses were poking up from the water all around us. We paddled deeper into the shallows until we came to a spot that my brain said, “This must be the narrow passageway we’re looking for.” It was a little muddy ridge that stood in between one shallow pond and another shallow pond. This was a little different than the other portages we’d done, but hey, nature isn’t symmetrical everywhere, right? We called it the “No-portage Portage,” because all we had to do was hoist the canoe over this one-foot patch of mud and we were back in a shallow pool of water. Easiest portage ever!

After this point, though, the shallows didn’t lead anywhere. They didn’t open up into another beautiful blue lake. The water started getting even shallower. The tall grass was getting thicker. It was getting harder to paddle the canoe. At first I thought, “we must just need to trudge through this a bit more,” but from the back of the canoe, Blake said, “something doesn’t smell right.”

This moment was the first time it occurred to me that we might be somewhere other than where we thought we were.

We decided to go a little farther before making any bigger decisions, but this bog we were in was no joke. It was a full on bog – part land, part water, all trouble. We’d have to dismount and walk because the water was too shallow, and we’d be lugging the canoe through the mud and then… whoop!… one of our legs would get sucked 2-3 feet into the mud. It didn’t take much of this before we stopped and really looked at the map to figure out where we were.

It’s a scary feeling, not knowing where you are in the woods. After some theorizing back and forth over a period of about 15-20 minutes, we concluded that we must have missed the narrow channel into Little John Lake, paddled the entirety of John Lake, and ended up in the bog in the northwest corner of John Lake.

In a way, this felt like a relief. Even though we’d spent the better part of an hour muddling through this bog, now we “knew” where we were. At least, I felt like we knew, because we didn’t actually know for sure. We couldn’t Google it. But, assuming we were right, it would take another 20 minute slog to backtrack through the bog, and then another little bit to repaddle south on John Lake, but hey, in the matter of maybe one hour, we’d be back on our planned route, and we still had enough daylight to make it to Pine Lake and make camp before sunset. This plan of action seemed like a no-brainer to me.

Blake, on the other hand, saw our situation differently.

Blake didn’t see our path as a “wrong turn.” Blake did not want to “go back.” Blake saw this as an opportunity for us to put our outdoorsman skills to the test. He pointed out on the map that there is a portage between John Lake and East Pike Lake. If we could just hike our way to this portage, which we should have been pretty close to, then we’d be able to get into East Pike Lake and paddle west back to Clearwater Lodge through the Pike Lakes. While the plan made a shred of sense, what made much more sense to me was to backtrack. We knew the way. If we marched forward, since we didn’t know exactly where we were, we didn’t know exactly where to go.

He convinced me to go “just a little farther” to see if it would clear up, get easier. Hopefully we’d see the actual portage soon. So we’d lug the heavy canoe a ways, stop, check the map, I’d say something like, “let’s just turn around” and Blake would reply, “just a little farther.” After 3 or 4 times of this routine, my internal alarm bells really started going off. We were losing daylight and not making any progress. I told him, “This is it. If it doesn’t open up to a clear path in the next five minutes, we’re turning back.” He agreed. He knew he had pushed me to my limit and that our situation wasn’t looking that good.

But in that last little five minute stretch, it did appear to open up a bit. And so in that moment he made a believer out of me. We could do it. We could break another rule I’d learned about hiking through the woods, which is–don’t leave the trail.

Life presents us with these moments, these fateful forks in the road, the moments when you realize you’ve gone astray and you’ve diverted from your intended plan. Do you retreat and get back on course, or do you press onward? These moments set the course for the next minutes, hours, and days of your life. Little choices like french fries or onion rings we may think only impact our next few minutes, but some choices turn out to be big choices, and they affect your following days, weeks, years, and maybe even your whole life. Maybe all of our choices actually impact us in this way. Sometimes, though, you can feel the weight of a choice, where the downstream impact is so obvious and so colossal that you can tell–this is a big decision. This was one of those moments.

So we could turn back, or we could break this tried-and-true rule about not leaving the trail, and we’d be OK because we “knew” where we were and we knew where we wanted to go and the path ahead looked easy enough and we were two strong, competent dudes that could do it.

I agreed to proceed. From that point on, in my mind, there was no turning back.

Five minutes later, I wished we’d turned back.

The hours that followed were the most grueling, rugged, terrifying hours of my life.

Here’s what we were facing. First off, we were both wearing heavy packs; mine was the heavier one, because our system on the normal portages was that Blake would carry the canoe, so he had the lighter pack. We dubbed my pack “Big Bertha”–I don’t know for sure but she probably weighed around 100 pounds. In order to get to a standing position with Bertha on, I needed to either set her up on an elevated log (ideal) or I’d have to squat down on the ground, put the shoulder straps on, and then Blake would need to hoist me up.

So we have the heavy packs, and we also have a kevlar canoe with our fishing rods cinched down to the inside of the canoe rim. In this unofficial portage we were in, sometimes Blake would have the canoe by himself overhead, and sometimes he would grab the front and I would hold the back and we’d do more of a lift-and-drag maneuver. (Not exactly textbook portage technique.)

We were in the bottom of a sort of ravine, a shallow valley, with slopes climbing upward on either side. At the bottom of the valley were thick brambles, these tough, spindly sticks all intertwined, making them virtually impenetrable. They didn’t have leaves and they didn’t have thorns, but as Blake would push through them at the front of the canoe, they’d bend and flex and then hurtle back toward my face with lightning speed–WAP!

After some rough going through the brambles, we eyed the slope to our left. There weren’t nearly as many godforsaken brambles up there. It was, however, up. It turns out going uphill in the Minnesota wilderness with a canoe and a 100 pound pack on your back is not a walk in the park. If the path would have been open and clear, the hill might have been manageable, but the path was not open, there were trees everywhere. When you’re backpacking, trees in your way are not a huge problem; you simply walk around them. When you’re backpacking with a canoe, though, the game is changed. They didn’t tell us this at the outfitters, but I discovered a universal truth about canoes in those woods–canoes don’t bend. In order to move forward, we had to find angles through the dense forest where we could move 17 feet of canoe in one direction without running into a tree. Turning was terrible. Many times we’d have to hoist the canoe vertically in order to get it around one tree and then, seconds later, be doing the same maneuver in reverse because of the next maze of trees just feet ahead.

The ground underfoot? Terrifyingly treacherous. It was late May in northern Minnesota. The ice on the lakes had just melted two days before we arrived at Clearwater Lake, so while the lakes were thawed and paddleable, the floor of this densely shaded forest was not entirely thawed. Occasionally we had to traipse through snow. Now, I’ve lived with snow my whole life. I’ve done pretty much everything there is to do with snow, including walk on it. But this snow, this was some tricky, deceptive-ass snow, which we learned the hard way. I would be walking on dirt, and then I’d be walking on snow, and then with my next step I’d lose my whole leg into a hidden three-foot snowhole–poof! Stepping into invisible holes is not an activity I’d recommend while carrying 100 pounds on your back.

When we weren’t walking on and falling through snow, we also had to contend with unreliable, decaying, moss-covered fallen trees and logs that lay blocking our path. Often there was no other choice but to walk over them. The wet moss was extremely slippery, and every once in a while we’d be treated to the gift of trying to step on and over a downed tree only to have our feet plunge right through the dead wood. It felt like only a matter of time before one of us sprained an ankle or twisted a knee.

They say that when you’re in the wilderness you aren’t supposed to fight Mother Nature, you’re supposed to go with nature, to listen and observe the rhythms of your surroundings and use what’s available to your advantage.

That sentiment is nice and all, but this. Was. A. Battle. A trial. Tough Mudder ain’t go diddly on this.

We fought. We trudged. We fell. We dragged this poor canoe under, over, and between so many goddamn trees and plants. At one point I had to Army-crawl through the cold muck with Big Bertha on to get under an enormous fallen tree. It was exhausting. We dug deep and pressed agonizingly slowly onward.

We had to get to East Pike Lake. Were there times I was cursing Blake in my mind for putting us in this position? Obviously. Those moments were fleeting, though. There wasn’t time nor energy to ruminate. Plus, I had chosen this. I had ultimately agreed to continue, and I had adopted the mindset that there was truly no going back.

Eventually, battered, bruised, sweaty, and filthy, we got to a point where the sunlight was really fading quickly. We knew we weren’t going to make it to any lake before nightfall. I didn’t want to make camp in the dark, especially since we were in the middle of an unfamiliar woods without the false sense of security an actual campsite gives you. It was time to make camp.

Blake then had an idea. What if he ran ahead to scout out our path for the next day, while I stayed behind to set up camp?

[Zack Morris-style Time Out.] You know how in every horror movie that was ever made, everything’s going along fine until the band of merry friends has the brilliant idea to… drum roll please… separate?! Well that is exactly what was going through my head at that moment. Sure, there were some merits to the idea. It would be helpful to scout ahead and see if, in fact, we’re headed in the right direction and to know how much farther we had to go until we reached a lake. But at what cost? In a horror movie, is anything the protagonists are trying to gain by separating ever worth the cost of being alone? Literally zero times. [Zack Morris Mode over.]

So of course, moments later, Blake is bounding off into the woods with nothing but an empty water bag, a headlamp, and a compass, leaving me at our “campsite” at the bottom of a brambly, unwelcoming forest valley.

Most everyone is familiar with the “fight or flight” survival response we have in our reptilian brains when confronted with danger, but there is a third survival response we have ingrained in us as well–freeze. With Blake gone, I went into freeze. I couldn’t make camp. I couldn’t do anything. I needed my companion, but he wasn’t there. I noticed I was frozen, and at first I told myself it was because I didn’t want to set up camp in a way he’d disagree with, but actually, that wasn’t the truest truth. The truest truth was that I had never been in this situation before. I didn’t know what to do. I was scared. How was I going to confront this actual survival situation?

I felt a wave of strong emotion swell. In hindsight, I am so thankful to have had some coaching and practice with emotions. I had some sense of what to do. I didn’t fight it. I let it in. I leaned into it. The emotion took over. I full-body bawled into the dense forest. No one was there to see me. I didn’t have to hide anything. All the tears and sobs and snot poured out of me. I tried to name the feelings. Fear. Anxiety. Worry. Uncertainty. They were all there. So many things could go wrong here.

The thought crossed my mind, “I could die in here.” These trees might be the last things I ever see. I may never see my kids again. I could feel the negative thought spiral swirl.

My meditation and gratitude practices kicked in then. It wasn’t the first time I’d thought about dying. I’d already practiced that. And I’d also practiced noticing my thoughts and feelings, noticing them as an observer rather than as the “self” that is experiencing them. As the observer, I could then see how this despairing thought of imminent death could grip someone else in my situation, but it didn’t take hold of me.

As I reconnected to my breathing, the sobs started to subside, and I recognized the fear, and I asked the fear–what are you so afraid of? Death? Pain? Being alone? I realized that it was indeed the fear of dying that scared me most, the notion that this would be my last day alive on Earth. OK, so I’m afraid today will be my last day. Hold on a sec. I still have food, I still have water, and I have all of our camp and survival gear. It occured to me that even if I never see Blake again, even if something close to the worst case scenario does happen, today is not the day I’m going to die. A few days from now, that might be a different story, but as long as I don’t get eaten by a bear, I have a really good chance of surviving to tomorrow.

That’s the idea that snapped me out of freeze.

“What can I do to make this situation a little better?” I thought. To hopefully attract Blake, but if nothing else to give me comfort, every five minutes I blew my whistle as loud and as long as I could for an entire lungful, took a deep breath, and then yelled, “Blaaaaaaaaaaake!!!!!” until my breath ran out. Then, after that release, after giving my body a sense of, “I’ve done what I can do,” I continued slowly setting up our tarp ropes.

This routine carried on for what felt like an eternity, but realistically it went for probably 45-75 minutes or so. Eventually, as dusk was setting in, one of my whistle blows was responded to! “I’m comin’, Gip!” replied Blake from a distance. Minutes later he approached with a pep in his step, a bag full of water, and a huge grin on his face. “I found the lake,” he beamed as he held the bag of fresh water up high. His news of our whereabouts should’ve brought me a huge sense of relief, but what was more relieving was simply to have his company again.

I sheepishly admitted I had been mostly useless during his scouting mission, but he was unphased by this. As the temperature continued to drop, probably into the low 40s that night, we finished setting up camp, ate some warm food, hung the bear bag, and prayed no large mammals would get cozy with us as we tried to sleep fast.

I slept with my camping knife extra close that night.

Day 5 – Saturday – Emergence From The Void

We woke up with sun. And the frost. It was cold, but we had purpose. We packed up swiftly, donned our packs, and continued trudging with the canoe toward our newly decisive heading.

Immediately we were reminded how miserable this was. Just because we knew where to go didn’t make the maneuvering any easier. It was hard, slow going. I started wondering how many hours we’d still be in this godforsaken valley until we finally reached the water.

After some number of minutes of this heavy, frustrating toiling, somehow we came up with what turned out to be the most genius, brilliant, mood-shifting idea of the entire expedition thus far – the idea to double portage. This meant we would leave the canoe in a (hopefully) findable location and hike with only our packs until we reached the water’s edge. Once there, we could dump our packs, backtrack to retrieve the canoe, and then we’d be able to navigate through the hills and underbrush without 50-100 pounds on our backs. The choice wasn’t without its trade-offs; we had to make sure we’d be able to find the canoe, and we would have to walk the distance twice instead of once. It was another one of those weighty decision moments.

What an absolute game-changer that decision turned out to be. If only we’d thought of that earlier. But then again, if we’d been able to think of double portaging earlier, we would have. It took that amount of struggle in order for our brains to think outside the box and get creative with an alternative way forward.

From that point it felt like we practically flew through the woods, Blake leading the way down the path he had scouted, his footprints in the snow and mud formed the night before guiding us to glory.

We made it to East Pike Lake, first with the packs, and then with the canoe. A lake has never looked so beautiful in my entire life. But we weren’t out of the woods yet.

We were not at an official portage. We had bushwhacked. That meant that instead of crossing from one lake to the next at the lowest elevation point, we were up on a cliff. We had to get our bodies, packs, and the canoe down roughly 50 feet of drop-off with no discernible path to follow. Normally this would have terrified me, but now, after making it through what we’d just gone through, it just seemed like the next thing we had to do, the next task to complete. We shimmied and tacked down the ridge ever so delicately until we reached the water’s edge.

If I knew how to backflip, I would’ve done so at that moment.

The paddle westward across East Pike Lake was the most glorious canoe ride I have ever experienced. To be able to float and glide along the water after needing to bulldoze and carry, well, it felt like heaven.

Once we arrived at the portage into West Pike Lake, it seemed obvious to me that we would continue into West Pike, which would be the final lake we’d have to traverse before a final portage into Clearwater Lake, our destination. As you might expect by this point, Blake had other ideas.

“Take a look at the map,” he encouraged. (The only map we had left, mind you, because he had lost our other one.) “There’s another portage southward which gets us into Pine Lake, which connects to Caribou Lake!” Now, we had been told at the beginning of the trip by the outfitter that Caribou was one of the nicest lakes in the area, also good for fishing and that there was an interesting falls area somewhere nearby, so that’s why it was on Blake’s radar. The difference in routes, though, was that if we went through West Pike (my way), we’d only have one more portage, but if we went the Pine and Caribou route (Blake’s way), we’d have three more portages, and not only that, but the portage from East Pike to Pine was almost 400 rods long (400 canoe lengths) and rated a Level 10 out of 10. This portage was the farthest and the hardest of any other portage on our entire map, and Blake wanted us to choose it after all we’d been through.

So we did.

It was an incredible feeling, doing that portage. At the beginning of our trip, if we’d been confronted with this choice, there is zero chance I would have agreed to do the Level 10. But after bushwhacking through the wild, it honestly felt like child’s play. Sure it was far, and sure it had some tough terrain at parts, but it was still an actual trail. It felt like a treat to be able to schlep all of our stuff through an intentional, somewhat well-trodden path. I finished that portage feeling like a hero.

We paddled some more, the wind at our backs, and made camp around 8pm at the most gorgeous campsite ever created. OK, it was probably an average campsite, but in my eyes, with an open clearing with a fireplace, a nice flat rock leading down to the water I could walk barefoot on, and a sunset view over a gorgeous northern lake, it felt like a million dollar home. In fact, it felt so swanky, we dubbed our final camp setup “The Belaggio.”

Day 6 – Sunday – Homeward Bound

We were still way up in the Boundary Waters, and I was supposed to be home for dinner Sunday night. We had some work to do, but our bodies needed some slow movement Sunday morning. We finally packed up and left The Belaggio around noon, and carried on toward Clearwater Lodge.

We attempted to find the falls around Caribou Lake that the outfitter had mentioned. No, there wasn’t a well-worn trail for us to take there. So we bushwhacked. Again. This time, though, without the canoe and our big packs, just a light pack for a final romp through the woods. We traversed a slope for some time, pushing our way through more brambles and thorns, until finding… a tiny little creek bed. Not quite the epic falls we were hoping for, but it felt good to tack on some extra difficulty to our already insane journey.

We portaged into Clearwater Lake, and as we paddled to the outfitter, a small motorized fishing boat was heading toward us. As they got closer, we realized it was the guy that works at the outfitter. He was looking for us! We were arriving at the lodge a bit later than expected, and Kristyn had called in to check on us. Had we made it to the lodge an hour earlier, I would’ve been able to call and let her know everything was alright, but alas, we didn’t make it in time for that. After the first wave of embarrassment passed, it actually felt nice to know that someone out there was keeping tabs on when we should’ve been emerging from the wild. I was sure she wouldn’t be pleased with our late arrival home, but I hoped that once she heard the story she’d be happy I was still alive. (She was.)

The Aftermath

When you spend time in the woods, away from screens and electricity and traffic, it changes your perspective. I’d experienced this before. This time, I’d not only camped–I’d had a wilderness survival experience. It definitely changed how I viewed the world in the days immediately following our expedition.

The first morning in my house, you would think I would’ve slept until noon, but no, I was up before the rest of my family, and I felt an immediate pull to go outside. I sat on our back deck, which faced a wooded wetland area, and sat down to meditate. The birds were chirping loudly, and typically when I would sit out here in the morning it would be the bird songs that would capture my attention. Not this morning. This time I immediately noticed how much louder the distant highway traffic noise sounded in the distance than it normally does. It was this foreign, man-made disturbance to nature’s common audio field that was catching my ear after having been subjected to nothing but nature’s auditory offerings for the past six days.

My body did need to recover that day, but one day of rest was all my body was interested in. The next day I filled up my 60 liter pack with pointless stuff, I just wanted to get some weight into it, and I went out to the hiking trails behind our house to run hills, all before breakfast. This is not something I was doing prior to the Boundary Waters, but after what I’d just gone through, it felt easy. Normal. Like what I was supposed to be doing. I’m sure I looked like a nutcase to the casual walkers I passed by.

I felt like reading or listening to podcasts didn’t interest me. I didn’t need any more “new” in. I had just been living a life of… being alive. I had just touched some deeper truths, some realer version of the real world.

I felt more like a human. Like those of the generations before me who didn’t have GPS, the internet, and all this high-tech survival gear. I could feel the beautiful balance in my body from rowing the canoe in a seated position to rucking around with a heavy pack in the portages. As soon as I was really feeling ready to stop paddling, it would be time to portage again, and vice versa. Every change was welcome. I actually felt in my bones a taste of what it must’ve felt like for the people who first explored and inhabited these lakelands.

And, in the days after my return, I had a newfound love of the simplest things in our home, like our refrigerator and the miracle of a working faucet.

A FEW LEARNINGS

These were the top lessons I take with me from my time in the Boundary Waters:

- If you’re gonna whack some bush, wear gloves. Your hands will take the most beating.

- If you don’t have gloves and you have a free hand, you can use hold a large water bottle or a large carabiner to push brush out of the way so your hands don’t have to do all the dirty work.

- If a portage is too intense, you can always drop the canoe and double portage.

- Doing really hard things sucks in the moment and feels really damn good afterwards.

- I know more than I think I know.

- I know how to pick a good campsite in the wild.

- I know how to burn wet wood.

- I know how to ration water.

- I know how to read a topographical map.

- I know how to read the land and find the pathiest paths.

Most of all, the biggest life lesson I learned was this:

There is no such thing as a “bad decision”–there are only trade-offs.

All the choices we made on this journey, whether to paddle to the next lake or not, whether to take this route or that one, whether to have a relaxing day to fish or move some extra miles, whether to retrace our steps or venture onward into the unknown… whichever way we chose would work out. There wasn’t a “right” decision and a “wrong” decision. It all comes down to trade-offs. If we choose to take it easy and fish, it means we have to paddle more the next day, but we have a chance at grilling up some tasty lake trout that evening. If we skip the fishing, no chance at lake trout, but we have easier paddling each day. Neither option was wrong.

This insight sticks with me. It relieves the pressure of decision-making, removing the idea that if I just analyze my options a little bit more I will uncover which one is the best, most perfect, most right choice. It’s not about getting it “right.”

It’s about doing my best with what I know at the time, accepting whatever comes after, leaving the rest behind, and knowing that I can always make another choice in the next moment.

I always thought they called it the “Boundary Waters” because it’s on the boundary between the United States and Canadian borders.

Now I believe it’s because it’s a place where one can to go expand their boundaries. I know I did.